The following article was written by Ben Saul, Associate Professor of International Law at Sytdney University. It first appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, Monday June 7th.

In Franz Kafka’s novel The Trial, an ordinary man finds himself trapped inside the byzantine processes of a shadow justice system. When he asks what he has done wrong, the bureaucrats reply, “It’s not our job to tell you that.”

When he goes to court, he and his lawyers are not allowed to see any of the evidence against him.

His faceless accusers always remain unknown to him. Inevitably, in a system such as this, he is found guilty. All around him, life continues as normal, as if the fair trial of one man is of no concern to the world.

Kafka’s story is a terrifying glimpse into a world which, on the surface, claims to be ruled by law, but in reality is one where the modern bureaucratic state exercises total control over the individual. The individual’s right to be treated decently is extinguished for an unknown greater good. Kafka was writing about rising authoritarianism in early 20th-century Europe, but he could well have been describing Australia’s migration and security laws.

Mansour Leghaei is a long-term resident of Australia soon to be deported to Iran on national security grounds. All he has been told by the intelligence agency ASIO is he is a risk to national security. He has been shown no evidence by ASIO or in any of the court proceedings he brought to challenge ASIO’s assertion.

Absurdly, he has received letters from the authorities asking him to answer the allegations against him, when he has no idea what they are. A Federal Court judge observed his right to procedural fairness had been reduced to ”nothingness”.

Because Australia has no bill of rights, in Leghaei’s case, Australian law cares nothing for the right to a fair hearing of foreigners in security cases. This places Australia in direct breach of its international law obligations under the human rights treaties which it agreed to. Human rights law recognises the importance of a country’s security concerns, but requires minimum guarantees of fairness for an affected person.

The Australian approach is at odds with much of the liberal democratic world. In Britain and continental Europe, which face greater security threats than Australia, human rights law requires a person to be told the substance of the allegations. Sources and informants and other sensitive information can be protected, but an affected person must always receive a summary of the reasons and evidence. That delicate balancing of interests is a sign of living in a civilised society bound by the rule of law.

The denial of a fair hearing is foreign to our ancient common law tradition. The common law depends on an adversarial process, in which a person can challenge the evidence against them. Only be exposing allegations to the harsh light of day can their truth be tested.

Allegations may be false, informants may bear grudges, conduct may have innocent explanations, and intelligence may be misinterpreted. Few can forget that Iraq was invaded in 2003 based on botched intelligence; no reasonable Australian can have blind faith in ASIO.

Where a person is unable to see or test the evidence, it cannot possibly be determined whether the person is actually a risk to national security or not. Deporting Leghaei in such circumstances would be arbitrary, capricious, and internationally unlawful.

It would also deprive Australia of a moderate religious leader and voice of tolerance, as well as depriving his children, who are Australian citizens, of their father. As a Federal Court judge said: “His deportation may well cause hardship to utterly blameless Australian citizens and permanent residents”.

For that reason, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has ordered Australia not to deport him until the UN has ruled on his complaint against Australia.

The UN’s temporary order aims to prevent the ”irreparable harm” to the Leghaei’s family life which will result if he is torn apart from his wife and children – including his 14-year-old daughter, who will lose her father – by deportation. The UN’s order is binding under international law, necessary to ensure the procedural integrity of the complaints system.

While the Rudd government talks the talk of human rights and global governance, signing up to every treaty under the sun, it is in individual cases the rubber hits the road.

By announcing that it will deport Leghaei in defiance of the UN’s order, the government has revealed its true colours and its contempt for international law.

Its commitment to the UN system is flaky and selective. Kafka Kevin’s hypocrisy is remarkable, particularly when a tedious and splenetic Opposition turns up the heat on immigration.

Leghaei’s request of the government is not radical: tell him what he has supposedly done, let him explain it, and only then deport him if the allegations are true.

That is what a fair and civilised society ruled by law would do.

No Australian can have confidence in our security where it is based on faceless accusers and secret evidence – and where ordinary people are judged in the shadow of the law.

Assoc. Professor Ben Saul

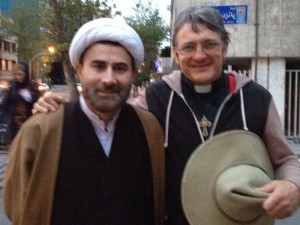

Father Dave Smith

Father Dave Smith